Alvin Ailey and Romare Bearden

Posted February 21, 2024

During Black History Month, Ailey is highlighting artists from different disciplines—music, poetry, visual arts—whom Alvin Ailey collaborated with and whose own works explore Black American cultural heritage. The second artist we’re spotlighting in this series is visual artist Romare Bearden. Ailey and Bearden sustained a decades-long friendship which culminated in fruitful collaborations, as well as one major project that never was.

In the 1980 documentary Bearden Plays Bearden, the artist Romare Bearden talks with novelist James Baldwin, critic Albert Murray, and Alvin Ailey—the four long-time friends sitting together in a small living room, discussing life and art. Like an eager protégée, Ailey excitedly peppers Bearden (whom he calls Romie) with questions, wanting to hear his reminiscences on the Harlem Renaissance and Paris in the 1950s. Bearden answers like a patient father figure. At the time of this documentary, Ailey and Bearden had been friends for years. Both made art that captured the vibrancy and friction of Black culture—the ancestral colliding with the everyday—complementary influences that made them natural collaborators. Bearden created costumes and sets for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. What might have been their greatest collaboration, however, now only exists in a collection of Bearden’s paintings.

Albert Murray, Romare Bearden, Alvin Ailey, and James Baldwin in

Bearden Plays Bearden (1980). Director Nelson E. Breem.

Bearden was born in 1911 in Charlotte, North Carolina, but grew up in Harlem in the 1920s, when artists were redefining African American culture on their own terms. From the poetry of Langston Hughes to the swing dancing at the Savoy Ballroom, Jazz rhythms infected everyday life and eventually found their way into Bearden’s art. His work focused on the artists, musicians, poets, and other denizens of Harlem. While he worked in a variety of visual art mediums, Bearden is most widely known for his collages of fragmented and juxtaposed textures and colors that evoke the jazz and bebop music he grew up with.

After spending the ’50s in Paris where he befriended James Baldwin and did little painting as the city kept him too busy with parties, Bearden returned to New York in the early 1960s. He rented a room in Harlem for $8 a month and made an immediate impression on the city with his artworks’ bold renditions of city life.

Bearden first partnered with Ailey for the Duke Ellington tribute at Lincoln Center in 1976. He allowed his work to be projected on stage as a backdrop to Duke Ellington's son Mercer Ellington leading a band playing his father’s music. It’s fitting that music was the entry point to their collaboration. “There’s so much music in Romie’s work,” Ailey said. “There’s so much blues, spirituals; there’s so much gospel. There’s so much Mobile, Alabama, so much New Orleans, so much Mahalia Jackson.” Bearden’s wife, Nanette Rohan Bearden, was also a dancer and choreographer who founded her own company in 1976 and instilled an appreciation for dance in Bearden.

Alvin Ailey and James Baldwin in Bearden Plays Bearden (1980). Director Nelson E. Breem.

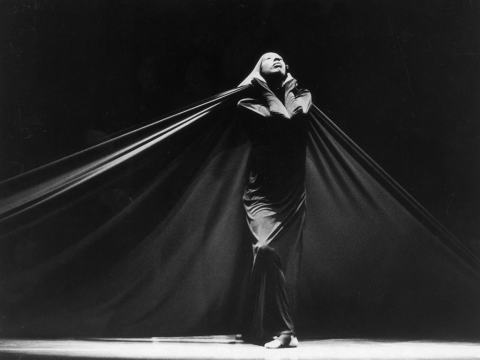

The year 1977 marked Bearden’s first direct collaboration with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. He created the costumes and sets for Dianne McIntyre’s work Ancestral Voices, a contemporary take on African ritual dances. For the set, he designed a large curtain made of foliage and what The New York Times called “African forms.” No images survive of Bearden’s creations, leaving what they looked like—most likely a collage of forms draped together—up to the imagination. Bearden also designed set pieces for Alvin Ailey’s Passage, a solo for Judith Jamison, in 1978. The dance starred Ms. Jamison as “the most powerful voodoo queen in the history of this country.” However, Bearden did not create costumes in line with his usual brightly colored works, instead he created starker designs for the Africanist subject matter. Reminiscent of Martha Graham’s Lamentation, he dressed Jamison in swaths of purple fabric and his set pieces were limited to rudimentary beam-like platforms for her to stand on. Bearden also created a cityscape backdrop for Talley Beatty’s Stack-Up that Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater premiered in 1982, as well as scenery for Talley Beatty’s Blueshift from 1983.

Judith Jamison in Alvin Ailey’s Passage. Photo by Johan Elbers.

Bearden’s sets and costumes complimented Ailey’s dances, but in the late ’70s he proposed a far more collaborative project, a new ballet that Bearden dreamed up in a series of collage paintings called Bayou Fever.

Created in 1979, Bayou Fever is a collection of 63 gouache and watercolor collage paintings inspired by Southern African American culture and Caribbean religious rituals. The works depict vibrant Southern landscapes—deep blues and greens of the marshy bayou, a farmhouse sitting under a lightning-forked sky, and enigmatic figures wearing headdresses and skirts in African prints. The Bayou Fever collection was conceived as the inspiration for a new ballet, one that Ailey would choreograph and Bearden would design. Sadly, the collaboration never came to fruition. From looking at Bearden’s paintings, one can imagine how brilliant the work might have been.

Ailey and Bearden both translated their personal experiences and shared Black heritage through modern art practices that they repurposed for their own means. In Bearden Plays Bearden, Albert Murray tells Ailey:

“I would say that you yourself are the very embodiment of the process we are talking about. You studied dance under Lester Horton, a very sophisticated exponent of modern dance, a pioneer, a man who was pushing back the language in terms of contemporary statement. He was avant-garde, if there was such a thing. And yet, what you did with it immediately was to give to the anthology of dance, of choreography, Revelations and Blues Suite. In other words, you were processing experiences from Texas, Newport, or L.A. into fine art, and you did it by using the broadest possible language of movement. This is the sort of thing Romare was doing in Paris.”

This underlying reason for why they made art was a source of Ailey and Bearden’s deep connection, a mutual understanding that linked them as much to history as to each other.

Romare Bearden. Photo by Carl Van Vechten.

Read more about Alvin Ailey's collaborative relationships on the Ailey Blog, including the first article in this series on Mary Lou Williams