Alvin Ailey and Mary Lou Williams

Posted February 14, 2024

During Black History Month, Ailey is highlighting artists from different disciplines—music, poetry, visual arts, etc.—whom Alvin Ailey collaborated with and whose own works explore Black American cultural heritage. The first artist we’re spotlighting in this series is jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams. Mr. Ailey worked with Williams on only one occasion, when he created a work dedicated to her legacy and musical innovation, called Mary Lou’s Mass.

Mary Lou Williams was one of the most sought-after jazz and bebop musical arrangers of her generation. On the piano, she pioneered a style of improvisation and super speed that many others took as inspiration. Her dexterous fingers could punch out complex harmonies on the keys—one hand keeping rhythm with ragtime or swing standards while the other danced through melodies borrowed from classical music—or she’d just slam a hand down for a chromatic crash. Her arrangements ran the gamut from free-wheeling swing numbers to orchestral arrangements for the New York Philharmonic. “I try to write music that would give peace to the soul or the heart,” she said in a 1971 interview. She wrote arrangements for the titans of jazz—Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman—and became a mentor to bebop musicians including Thelonius Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker.

Unlike the other jazz legends, Williams was a woman, making her ascendancy in the male-dominated world of 1930s and ’40s jazz all the more remarkable. Her reputation, immense to her fellow musicians, was less acknowledged by the public in her own lifetime. When Williams collaborated with Alvin Ailey on a major ballet titled Mary Lou’s Mass in 1971, some of the dancers, including a young Judith Jamison, confessed to not fully recognizing her impact. “She didn’t get her due,” Ms. Jamison said. “It was the wrong era.”

Williams was born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1910 and moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania when she was four with her mother and stepfather. Her mother taught her how to play the piano and she was so talented, Black neighbors paid her to play at their parties. When her family first moved into the neighborhood, white neighbors tossed bricks through their windows. However, once they heard Williams play, the harassment stopped.

As well as ragtime and boogie-woogie Williams played classical piano. She listened to records of Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines to expand her formal musical education. By age 15, she was already touring with small vaudeville bands. She often had to prove herself to bandleaders who didn’t want a woman on the piano, but her clear talent won them over.

Her first husband, saxophonist John Williams, featured her in his band, billing her as “The Woman Who Swings the Band.” In her second marriage, to trumpeter Harold “Shorty” Baker, she once again defied those who thought a woman wasn't suited for playing jazz piano by also starring in his band. Her arrangements for other swing musicians became jazz standards: “Roll ’Em” for Benny Goodman, “Trumpet No End” for Duke Ellington, and “In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee" for Dizzy Gillespie. In 1945, she composed her epic jazz symphony "Zodiac Suite," a piece in twelve movements matching the zodiac signs with influential artists, musicians, and dancers. “Scorpio,” for instance, is partly dedicated to Katherine Dunham while “Capricorn” is inspired by Pearl Primus, both of whom were influential choreographers and anthropologists at the time.

Williams first dreamed of collaborating with Mr. Ailey in 1965, when the two were supposed to work together on a concert in Pittsburgh arranged by John Cardinal Wright. Mr. Ailey couldn’t commit to the project, but the idea of a collaboration stayed with them both. “I’ve always wanted to do something with Alvin,” Williams said. “The first time I saw his work I went out of my mind.”

Kelvin Rotardier (center) in Alvin Ailey's Mary Lous Mass.

Photo by Rosemary Winckley.

In 1970, Mr. Ailey began work on a ballet entirely dedicated to Mary Lou Williams’ music titled Mary Lou’s Mass, what he later called “one of the great creative experiences of my life.” The work, danced to her “Music for Peace,” combined both Williams’ and Mr. Ailey’s deep affinity for blues, swing, and gospel music along with the culture of the Southern Black church. During the performances, Williams conducted the musicians and the dancers from the piano in the orchestra pit.

Mary Lou’s Mass premiered in 1971, the same year as Mr. Ailey’s work Cry. Having converted to Roman Catholicism in 1957, Williams' new ballet coupled her religion with her dedication to jazz and educating people about its African American roots. Mary Lou’s Mass contains twelve sections, each paired with a movement that mirrors Catholic Mass: "Entrance Hymn,” “Offertory Psalm,” and “Communion Song.” Just as her music brings in Black musical influences, Mr. Ailey pulled influences from jazz music into his choreography.

Judith Jamison and John Parks in Alvin Ailey's Mary Lou's Mass.

Photo by Rosemary Winckley.

Because it combined influences from Black spirituals and the church, the ballet was positioned as a companion to Revelations. Although it received an enthusiastic reception, Mr. Ailey himself was never fully satisfied with the work.

In 2010, near the end of Judith Jamison’s tenure as Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, she brought Mary Lou’s Mass back for the first time in 37 years. Associate Artistic Director Matthew Rushing, who performed in Ms. Jamison’s restaging of the work when he was a dancer in the Company, said, “As I was learning the steps to Mary Lou’s Mass, I felt as if I was getting to know Mr. Ailey in yet another way.” Knowing that many people still didn’t know Williams and her major contribution to jazz music, Ms. Jamison wanted to give the jazz great the attention she deserved.

In that sense, Mr. Ailey’s hopes for the work were met. “One of my plans in life is to identify Black music,” he said in 1971, “to make it audible.” With Mary Lou’s Mass, he has shared Williams’ brilliant musicianship with more of the world.

Learn more about Mary Lou's Mass

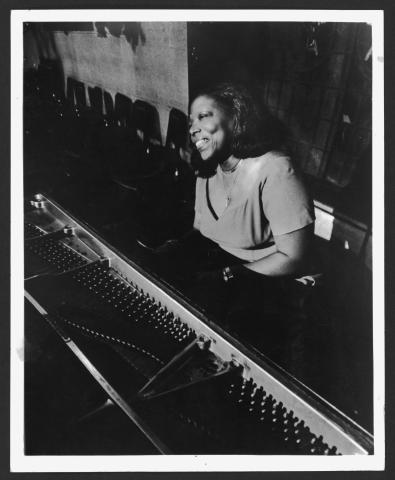

Mary Lou Williams. Photo by Peter Moore.