Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Among the diverse range of 25 works performed by the Ailey company this season is Uprising, an intensely powerful work created by the acclaimed Israeli-born choreographer Hofesh Shechter. New York Times critic Debra Craine wrote that “there isn’t a nerve left untouched” by the work, which has been described as evoking the aggressive and vulnerable facets of men. “It felt like unleashing a dog into the park,” said Shechter in an interview describing the creative process. In creating the all-male ensemble piece, he said he wanted to explore the limits of the dancers’ physicality. Ailey company members Glenn Allen Sims and Marcus Jarrell Willis shared with us their experiences preparing for the challenging piece.

Sims, who is celebrating his 17th year with the Company this season, said that all of his life experiences prepared him for the work. “I grew up in Long Branch, New Jersey and I had to defend not only myself, but my younger brother. I'm a husband and I've had to defend my wife. Basically, when we are pushed to a limit where aggression begins to show itself, the aggression that manifests from that is a natural reaction. So as an artist, you are compelled to highlight another aspect of yourself, a true side of who you are and not some put-on façade of ‘I'm an aggressive man.’” Willis said aggression is just one of male characteristics that Shechter was able to capture in his work. “I think the most prominent is the sense of humanity as a man,” he said. “The strength [as well as the] vulnerability of these men pave the way to a journey for both the artists and the audience. Understanding that I am one of the men on this journey has allowed me to embody the concept of the work.”

The Company in Hofesh Shechter's Uprising. Photo by Paul Kolnik

Shechter originally choreographed and set Uprising on his own company in 2006, relying heavily on improvisation from his dancers to develop the work. Because of this, what audiences will see from Ailey this season will not exactly resemble the original premiere of Uprising from years ago. Bruno Guillore, a member of Shechter’s original cast, reset the work on Ailey and allowed the dancers some artistic license while still staying true to the integrity of Schechter’s choreography. The improvisation is confined to specific moments determined by Shechter, a process Guillore has described as an exploration of “calculated risks.” The dancers, he said, “let themselves go; they are quite wild in the small moments of improvisation. That creates the excitement. It looks like a lot of the movement is random, but it’s not; in fact, the only parts that are improvised are short solos, maybe two counts of eight at most.”

Willis noted that the emphasis on improvisation made him feel more connected to the work. Uprising, then, is not being “recreated” by Ailey dancers, but rather “customized,” he said. Sims agreed, stating that Bruno’s use of improvisation in rehearsals gave the dancers not only the “artistic license to explore [their] own creativity, but [also] an opportunity to delve deeper into the work.”

Despite the fact that Uprising has previously been performed by other companies, Sims and Willis did not try to mimic other interpretations. Willis noted that his experience learning the piece was “a mixed, yet unique” one, as he had seen the work performed before. “I was more captivated by the work as a whole, so I didn't try to dissect or analyze it,” he said. “Apart from the mood of the piece and what I felt after seeing it, I brought myself into the studio as a blank canvas when we began. The information and direction from Bruno has been enough, and as a result the experience I have encountered thus far has revealed itself on its own.” Added Sims, “I’d rather take the steps taught to me in the studio and allow them to teach me how I should interpret the movement, thus making it my own, and therefore making it true for me.”

The Company in Hofesh Shechter's Uprising (Marcus Jarrell Willis pictured in red). Photos by Paul Kolnik

Sims said the work excites him, noting it “not only demands much of your own physical strength, but the vulnerability to rely on someone else’s strength to pull you through.” Willis said he eagerly awaits the development of the work over time. “The journey of where this will take me each time we perform and experience the work is something I'm looking forward to.”

Look out for Sims, Willis, and the rest of the Ailey company as they present 39 thrilling performances this season at New York City Center, now through January 4. www.alvinailey.org/citycenter

Interview conducted by Mykel Nairne.

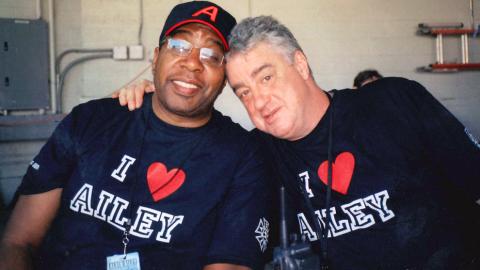

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Ailey Board of Trustees, and staff mourn the untimely passing of two longtime members of the Ailey family: E.J. Corrigan, Technical Director, and Calvin Hunt, Senior Director of Performance & Production, who died within a week of each other in the spring of 2014.

Calvin Hunt, left, and E.J. Corrigan, right, during the 2010-2011 Ailey season. Photo by Guido Goldman

E.J. Corrigan made many valued contributions to Ailey's performances since joining the production team in 1988, but he most cherished his self-appointed position as "head of morale," for which he was revered. His tradition of joyous barbecues in tour cities with Ailey dancers and crew and their local counterparts, along with his adventurous spirit, will be greatly missed. Generous of heart, he once biked coast to coast to support those dealing with catastrophic illness. E.J. loved the Ailey company and enjoyed each day to the fullest. Our hearts go out to his daughter Ana Luisa Corrigan, and all his family and friends.

In 1982, at the invitation of Alvin Ailey, Calvin Hunt joined the production staff and over the next three decades he became a pivotal leader within the organization, working closely with Artistic Directors Judith Jamison and Robert Battle. Calvin played an integral role managing Ailey's tours around the world, extending Ailey's role as a cultural ambassador. Calvin had an unparalleled love for Ailey and a passion for life. His sense of humor, wise counsel, and warm friendship will be deeply missed. He was an extraordinary man whose passing is a great loss to the Ailey family and the world of dance. Our hearts go out to his wife Margaret, their two children Eli and Brenna, and his entire family.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater celebrated the lives of E.J. Corrigan and Calvin Hunt at New York City Center on May 20, 2014. View videos from the memorial service:

- Excerpt from Grace, choreographed by Ronald K. Brown. Performed by Linda Celeste Sims, Demetia Hopkins, Matthew Rushing, Antonio Douthit-Boyd, Vernard J. Gilmore, Glenn Allen Sims, Daniel Harder, Kirven Douthit-Boyd, Belen Pereyra, Ghrai DeVore, and Rachael McLaren.

- Remarks by Bennett Rink, Executive Director

- Remarks by Joan Weill, Chairman of the Board of Trustees

- Remarks by Robert Battle, Artistic Director

- Remarks by Al Crawford, Joe Gaito, Dacquiri T'Shaun Smittick, and Kristin Colvin Young

- Remarks by Judith Jamison, Artistic Director Emerita

- Video Memories of E.J. Corrigan and Calvin Hunt

- Excerpt from Opus McShann, choreographed by Alvin Ailey. "Doo Wah Doo" performed by Matthew Rushing and Glenn Allen Sims.

- Excerpts from Revelations, choreographed by Alvin Ailey:

"I Wanna Be Ready," performed by Guillermo Asca, music sung by Rachael McLaren and Marcus Jarrell Willis.

"Rocka My Soul," performed by Hope Boykin, Jeroboam Bozeman, Sean Aaron Carmon, Elisa Clark, Sarah Daley, Ghrai DeVore, Antonio Douthit-Boyd, Kirven Douthit-Boyd, Renaldo Gardner, Vernard J. Gilmore, Jacqueline Green, Daniel Harder, Jacquelin Harris, Collin Heyward, Demetia Hopkins, Megan Jakel, Yannic Lebrun, Michael Francis McBride, Akua Noni Parker, Belen Pereyra, Samuel Lee Roberts, Matthew Rushing, Kanji Segawa, Glenn Allen Sims, Linda Celeste Sims, Jermaine Terry, and Fana Tesfagiorgis.

Notes of condolence may be shared here:

Sign the Guest Book for E.J. Corrigan

Sign the Guest Book for Calvin Hunt

"It is with profound sadness that we report the deaths of two integral members of the production team at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater...Dance companies, even ones as big as Ailey, are like families: The reason you like what you see onstage has much to do with what happens behind the curtain." --Gia Kourlas, Time Out New York

"RIP: Calvin Hunt and E.J. Corrigan of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater"

"These were two of the smartest, kindest, most dedicated men I have known. Their commitment to the Ailey organization was unrivaled...And now we are all crying together. And remembering our youth, our better selves, our friends." --Michael Kaiser, Huffington Post

"Calvin and E.J."

Now in his third season as Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Robert Battle has been applauded for broadening the Ailey repertoire with works by both established and up-and-coming choreographers.

The Ailey dancers are being challenged like never before. With each new choreographer, the Company must adapt not only to different movement styles, but also to each choreographer’s unique process and personality.

This winter, the outcome of one choreographer’s distinctive process was revealed onstage during Ailey’s 2013 New York City Center season. In-demand Canadian choreographer Aszure Barton, deemed “audacious” by The New York Times, presented the world premiere of LIFT, inspired by her process working with the Ailey dancers and set to a new score by musical collaborator Curtis Macdonald. The Ailey Blog spoke to dancer Daniel Harder during the rehearsal process about Barton’s unusual choreographic methods, and how he rose to the challenge.

Reprogramming the Approach

“I’ve always had a cerebral-like process when it comes to learning choreography, but what is difficult is learning the choreographer’s style and aesthetic,” says Daniel. “I’ve never worked with Aszure before, but her process is very challenging for us. There’s a lot of repetition, which of course we’re used to, but there are also a lot of changes. We’re constantly reprogramming our approach to the movement.”

The Ailey dancers are usually given three weeks to work with a choreographer on a new work, but the Company spent five weeks developing LIFT. With this additional amount of time, Harder and his colleagues were able to engross themselves in Barton’s movement style, vision, and voice.

“A lot of the time, we’re forced to produce very quickly since the turn-around time from rehearsal to stage is so short, so for Aszure to have five weeks, it’s great for us. We can really have a connection with her and try to understand and throw ourselves into her aesthetic.”

An aesthetic, Daniel explains, that was not an easy one to harness –even as an acclaimed Ailey dancer.

“Walking into the first day of rehearsal, she gave us all notebooks and a rhythm. She suggested we write the rhythm down whichever way we would remember it best. On that first day alone, we probably spent close to two hours just going over the standard rhythm. But then she would add on different layers to it, separate it, and combine it, which became very challenging and very complicated, very quickly.”

Mind Games

Barton continued to throw new challenges into those rhythms and steps, challenges which Daniel believed are very exciting for audiences—and a mind game for him.

“I’ve never been one to write down steps or notate rhythms. I would say that I rely on muscle memory, because there’s that moment where, hopefully, your mind and body sync up. But with Aszure’s piece, who knows,” Daniel laughs. "I have to stay focused and continue counting."

Dancer Daniel Harder's rhythm notes for Aszure Barton's LIFT.

Staying Alert

No matter what it takes to master choreography as intricate and process-oriented as Barton’s, Daniel shares his two biggest tips for young dancers: Keep your eyes and ears open.

“Aszure doesn’t always have the most authoritative voice, so she might give a note to one dancer, but it applies to everyone. If you don’t hear the correction, then staying focused and keeping your eyes open will allow you to see the change. That way, you can go back and process it for yourself.”

Members of the Company in Aszure Barton's LIFT. Photos by Paul Kolnik

Interview conducted by Lucie Fernandez.

You asked, and Artistic Director Robert Battle has the answers. In our three-part Facebook Fan Question series, get inside Robert's head and discover his thoughts on choreography, music, artistic leadership, the future of dance, and more.

Part 1: Choreography

Part 3: The Future of Dance & Staying Resilient

Robert Battle on Artistic Leadership

Robert Battle with the Company. Photo by Andrew Eccles

Owen Edwards asks:

What draws your attention to a dancer in an audition room? What qualities capture your eyes first? Also, what makes you turn your eye away from a dancer in the audition room?

I really look for a dancer that has the technical proficiency to do what they are asked to do, of course. But I also try to look at a dancer, like Alvin Ailey said, that can express what is strange and different and unique, or even ugly, about the dance itself. Dancing is a vehicle to express oneself. So if all I see is movement and not the person moving, then that doesn’t interest me. I’m really interested in how this dancer is able to communicate through the movement. This goes back to the notion that we do all of this to speak to one another. So if the only thing you can do is execute the steps, then it won’t hold my attention. Sometimes you can draw that out of a dancer, and sometimes that’s just not that dancer’s particular interest. And that’s okay too.

Nicola White asks:

How important is it to keep the Ailey company's past alive as well as combining it with a direction for the future and how do you try and achieve this?

It’s important to keep the past of the Ailey company alive, because the past is the present. I don’t see any distance between then and now. When I think about a great work of art, it endures, and it is timeless. If it was true then, then it is true now, and it speaks to the audience as it speaks to me. The past is not a burden; it’s the reason why we are here in the first place, so I embrace this rich history of this marvelous company. How do I achieve that? By always challenging and engaging the audience, challenging and engaging the dancers, and finding work that falls in line with that mission. And, by certainly remembering the oft repeated quote by Mr. Ailey himself, who said that “Dance comes from the people and should always be delivered back to the people.” Judith Jamison carried that torch, and now I carry it. I try to do things that come from my own instinct and heart, and that’s how I achieve it. But as for the future, the story hasn’t been totally written yet – I’m still living it. So we’ll see. Ask me in 20 years.

Robert Battle on Music

Kirven James Boyd in Robert Battle's Takademe. Photo by Andrew Eccles

Linda Edmonds-Lima asks:

What music genre is your favorite to dance and choreograph to and why?

Generally, I like percussion because it moves me. It’s very much in your face – you have to deal with percussion in a way that’s very immediate and I love that. But I love all types of music, from classical to experimental. For one dance I choreographed, Takademe, the music is very different – it’s set to Indian Kathak rhythms. One time, an audience member said to me, “Your music is everything from Bach to bongos.” I like that! And I find that that is true – different types of music challenge me in different ways. I started as a musician by playing piano when I was very little, so I had an appreciation for music at an early age. So music is really what moves me, but all types.

Alena Dancerchk Logan asks:

When choreographing a dance which comes to you first, the music or the movement?

Usually the music is the catalyst and the movement sort of pours out of that. Generally, I don’t choreograph in silence; it’s a response to a piece of music. And I try not to just imitate the music – I try to add my own voice through the dance as if I were another musician performing the score.

You asked, and Artistic Director Robert Battle has the answers. In our three-part Facebook Fan Question series, get inside Robert's head and discover his thoughts on choreography, music, artistic leadership, the future of dance, and more.

Part 2: Artistic Leadership & Music

Part 3: The Future of Dance & Staying Resilient

Robert Battle on Choreography

Jessica A. Yirenkyi asks:

Describe the moment when you know/feel that your choreography is "ready" to be showcased to the public or performed.

You never really know when your choreography is ready. I think that you are always a little insecure about it. Usually, I don’t know until somebody else is in the studio watching it and I can feel the exchange between the viewer and the work. That lets me know whether or not it is ready, just by the energy in the room. But you’re never finished. It never feels complete in your own mind. You always think, “Oh, maybe I could have done that a little bit better,” and that’s just the nature of being a creative person.

Victoria Gwinn asks:

Do you ever get nervous when presenting your work?

I’m always nervous presenting work. I think once you get to the point where you’re not worried about presenting work or dancing or performing, I think you should probably look at a new career move. I’m always nervous, because of course there is that side of you that wants people to like what you do. I think that’s inherent in any performer, even if they don’t say so. But then again, I try just to support the dancers who are doing the work and so I try not to let them feel my nervousness and only my support, because at the end of the day that’s what it’s all about.

Rebecca DeButts Covington asks:

Do you ever feel the need to create work that will connect with your audience members or do you focus on other goals when you work?

I always want to make work – and to see work – that connects with the audience. I think one of the cornerstones of the Ailey company is that we connect with our audience; that’s why we have had such a vast audience for so many years. To me, the single most important thing about being a choreographer or dancer is communication. If the work does not communicate, to me it is not successful. That’s how I view it. It doesn’t mean that the audience has to love everything that you do, but just feel and experience what you do in a way that is visceral.

Ronald Bailey asks:

Where does your inspiration come from?

For me, inspiration comes from my dancers. These are some of the most marvelous dancers in the world that I get a chance to work with, and that inspires me to choose repertory I want to see them do. As a choreographer, I’m interested in what they think physically, and what their experiences are physically – that inspires me. So the inspiration really is, once again, people. Rather, it’s people doing some courageous act; that human quality is always what I connect with.

Above: Artistic Director Robert Battle rehearsing Takademe with the Company. Below: Robert Battle rehearsing Strange Humors with Antonio Douthit and Jamar Roberts. Photos by Paul Kolnik